top of page

Activist Judges are Blocking the Trump Agenda. There is a simple solution DEMAND BONDS.

THE PROBLEM

Activists are winning preliminary injunctions blocking almost every major Trump administration reform. These are pre-trial injunctions, meaning the blocked reforms may ultimately be upheld, just as the Supreme Court upheld the travel ban over a year after it was halted just weeks into President Donald Trump’s first term. But in the meantime the damage is done. The government is being forced to spend hundreds of millions of dollars continuing policies it has every legal right to terminate.

THE SOLUTION

Enforce Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c) that courts "may issue a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order only if the movant" posts a bond equivalent to "the costs and damages sustained by any party found to have been wrongfully enjoined or restrained."

LEARN MORE

This op-ed explains that the judges issuing the injunctions are themselves breaking the law.

They are failing to require the plaintiffs to post injunction bonds to compensate the government in case they ultimately lose. Such bonds are explicitly required by federal rule 65(c), but judges ignore it. Early on, liberal activists recognized the injunction bond requirement as a major obstacle and worked to sideline it. The Administration should announce it will only respect lawful TROs/Injunctions, meaning those that include a bond, as required by law.

PRESIDENT TRUMP TAKES ACTION

On March 11, 2025, President Trump signed a memorandum directing federal agencies facing injunctions to demand that the plaintiffs post bond as required by Rule 65(c). This would ensure coverage of potential costs or losses if the court later deems an injunction wrongly issued. Read the Memorandum here. But this does not solve the problem so long as activist judges continue to ignore their obligation to impose bonds as a condition of issuing injunctions. The Administration should announce that it will obey any lawful injunctions. But injunctions without proper bonds are not valid injunctions.

"The Administration should announce that it will obey any lawful injunctions. But injunctions without proper bonds are not valid injunctions. "

FAQs

-

Aren’t bonds discretionary? No they are mandatory. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c) states that an injunction may issue “only if” there’s a bond. Judges are just ignoring it and conservatives don’t insist.

-

Are the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure binding? Yes, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure “have the same force of law that any statute does.” In re Nat'l Prescription Opiate Litig., 956 F.3d 838, 841 (6th Cir. 2020)

-

The rule says a judge “may” issue an injunction. Doesn’t that make it discretionary? No. The “may” refers to the decision whether to issue an injunction at all. Once a judge decides to issue an injunction, the judge may do so “only if” there is a bond included.

-

Doesn’t the rule say the bond must be in an amount the court considers proper? Yes, but the court’s discretion is limited. The judge must choose an amount “proper to pay the costs and damages” should it turn out the defendant was wrongfully enjoined. That sum is not zero or de minimis.

-

Won’t this get turned around on Republicans? Conservatives suffer disproportionately from national injunctions. Between 2001 and 2023, two-thirds of all national injunctions targeted Trump’s policies. Deterring such injunctions is overwhelmingly beneficial.

-

What if judges set the bond to zero or nominal? The rule requires judges to choose an amount “proper to pay the costs and damages” should it turn out the defendant was wrongfully enjoined. That sum is not zero or de minimis. See, National Kidney Patients Ass'n v. Sullivan, Order, No. 89-5039 (D.C. Cir., Dec. 8, 1989) (remanding a nominal bond to district court to “set an 'appropriate bond’ and stating that Medicare had already paid over $18 million to vendors under the injunction, an amount for which the $1000 bond was ‘clearly inadequate to ensure repayment.’”)

-

Won’t activist judges just ignore this requirement? That’s why the Administration needs to say it will obey any injunction but only if there’s a bond. They can force the judges to obey the rules, so long as the public is educated on the bond requirement first so they understand that the Administration is entirely justified. Note as well that the “[f]ailure to require a bond before granting preliminary injunctive relief is reversible error.” Maryland v. USDA, 976 F.2d 1462, 1483 (4th Cir. 1992).

-

Won’t the public miss the nuance and just claim Trump is ignoring court? That is exactly the point of this website. To educate the public so they are won’t be misled by the rhetoric. Fortunately, it’s an easy case to make because the rule’s language and history are so clear.

-

Why hasn’t this been done before? Back in the 60s liberals realized that the bond requirement would be fatal to their legal activism and started working to sideline it. It seems conservatives did not realize the significance of standing up to them or never bothered to do the primary research. Until now.

-

Why is this important? This will stop the activism in its tracks because properly set bonds will be in the tens or even hundreds of millions. For example, a judge ordered the government to rehire some 25,000 federal employees. That would require a $200 million a month bond that the plaintiffs lose forever if the firings are ultimately upheld. The costs will be prohibitive unless the activists have a slam dunk case.

-

What should DOJ do? Tell judges that it will obey the law, but they must too. DOJ will obey any lawful injunctions. But, an injunction without a bond is void ab initio. The court is without power to issue it. The administration needs to say it will comply with these injunctions as soon as the plaintiffs post the bond required to cover the cost of compliance.

-

Can the government refuse to respect an injunction with no bond? Yes, because an injunction without a bond is void ab initio. The court did not have the power to issue it. See Hopkins v. Wallin, 179 F.2d 136, 137 (3d Cir. 1949) (describing a Rule 65(c) bond as a “condition precedent” to the issuance of a preliminary injunction.)

-

Hasn’t the Supreme Court says you must obey even a wrong injunctions? U.S. v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258, 293 (1854) states that “an order issued by a court with jurisdiction over the subject matter must be obeyed by the parties until it is reversed by orderly and proper proceedings. This is true without regard even for the constitutionality of the Act under which the order is issued.” However, that case refers to a valid injunction issued to enforce compliance with an invalid law. Here the injunction itself is invalid because the court did not follow the procedure required to issue it.

-

Isn’t there caselaw that says its discretionary? Liberal judges claim bonds are discretionary, but the rule text and legislative history prove otherwise. The 1911 Judicial Code granted judges discretion to require injunction bonds. However, in 1914, Congress explicitly repealed that provision, making bonds mandatory. The revised language of the injunction bond requirement is mandatory and that is how it was enforced for 40 years. Then, as liberal activists adopted litigation as a policy weapon, these bonds “which may involve very large sums of money,” emerged as a major “obstacle” to their agenda. Sympathetic judges came to the rescue by declaring injunction bonds discretionary. These demonstrably false claims trace back to a 1954 Sixth Circuit opinion. The court “reasoned” that the rule’s directive to set the amount of the bond at "such sum as the court deems proper" allows the trial judge to dispense with the bond altogether. The problem is that this is not what 65(c) says. The court deceptively edited the rule’s text by truncating the end which directs judges to choose an amount proper to pay a wrongfully enjoined defendant’s "costs and damages." A law review article savaged the decision, noting that there “was no other discussion of the point, by way of analysis, legislative history, or precedent, which, indeed, seems to have been wholly lacking.” The correct view is that of Maryland v. USDA, 976 F.2d 1462 (4th Cir. 1992) (“The decision whether to require a bond is strictly circumscribed by the terms of Rule 65(c). The rule's only exception to the security requirement exempts ‘the United States or . . . an officer or agency thereof.’ Failure to require a bond before granting preliminary injunctive relief is reversible error.” & Ftnt 20: “There are no other exceptions.”)

-

Doesn’t caselaw say there is a public interest exception to the bond requirement? Without any textual basis, activist judges have tried to concoct a public interest exception. We should not let them get away with it. It began in the ’60s with welfare recipients suing to remove limits on their benefits and environmentalists trying to block projects like the expansion of the San Francisco airport. Soon, judges were issuing injunctions without any bond if they felt the cases implicated "important social considerations." In a case involving union elections, the First Circuit fashioned a balancing test weighing factors including the impact on the plaintiff’s federal rights, the relative power of the parties, and the ability to pay. None of this finds any warrant in the code. At best, these policy considerations justify amending the bond requirement, not ignoring it. The claimed public interest exception also proceeds from the false premise that activist lawsuits necessarily serve the public interest. Huge swaths of the public support Trump’s policies on foreign aid, immigration and shrinking the federal workforce. To them, preliminary injunctions are thwarting the public interest not serving it. Accordingly, there is no moral justification for an exception to the bond requirement. Indeed, a D.C. Circuit panel which included then Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg rejected a district court’s attempt to find a “public interest” exception: The “district court suggested that the ‘public interest’ favors encouraging plaintiffs to challenge agencies' interpretations of their governing statutes. But this completely overlooks a key purpose of the bond and the presumption of enforceability — to make plaintiffs consider the damage they may inflict by pressing ahead with a possibly losing claim. The presumption expresses a judgment that already subsumes such generic policy considerations as the public interest in providing judicial interpretations of statutes.” National Kidney Patients Ass'n v. Sullivan, 958 F.2d 1127, 1135 (D.C. Cir. 1992)

-

What about cases without direct economic damages (e.g., birthright citizenship)? Whenever there are demonstrable compliance costs a bond is required. The government has armies of statistical experts trained to quantify the costs and benefits of regulations (e.g., clean air rules) even where those costs are not obvious. For example, in the birthright citizenship context, costs include eligibility for many welfare type benefits (e.g., medical care, housing, food stamps etc.). The Justice Department should include in its briefs expert cost estimates from government economists anytime a plaintiff is seeking a preliminary injunction.

-

Won’t enforcing the bond rule prevent judicial review of government actions? No. Plaintiffs who cannot afford to post these bonds can still challenge administration policies. But they will have to actually prove their case instead of scoring a quick pre-trial win that kills the administration’s momentum even if later reversed.

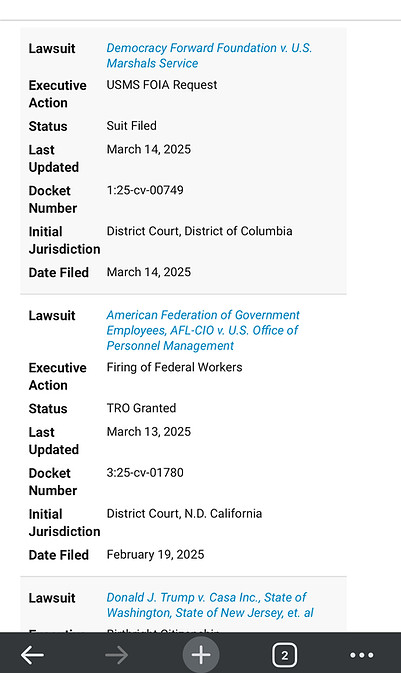

In the meantime, the activist judges are growing bolder. There are over 100 cases pending. Track the litigation here:

bottom of page